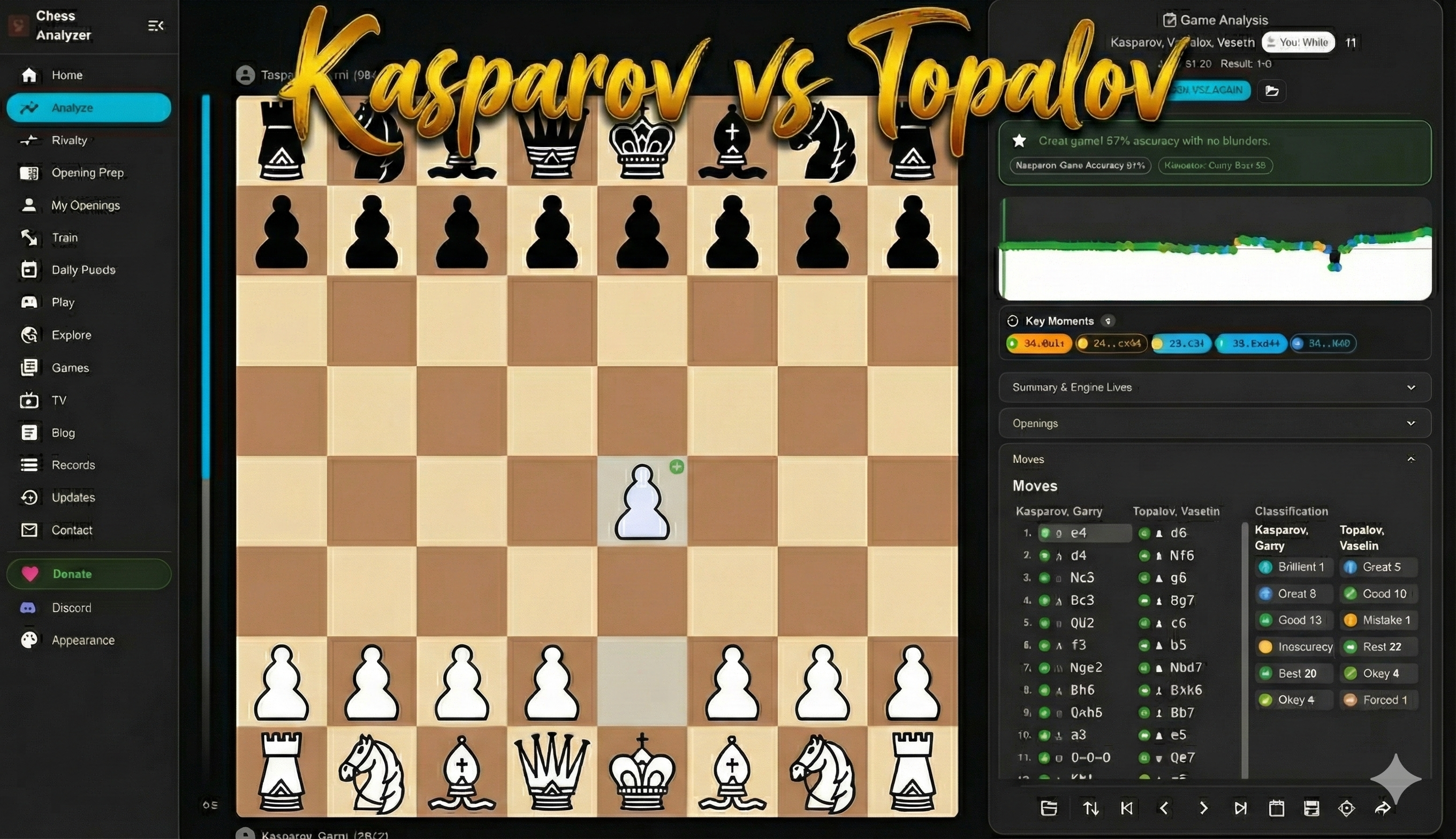

Kasparov vs Topalov 1999 Chess Analysis: The Immortal Game That Defined Modern Brilliance

A move-by-move breakdown of Kasparov's legendary game against Topalov at Wijk aan Zee 1999, featuring one of history's most spectacular king hunts and a series of stunning sacrifices.

The Immortal Game: Kasparov vs Topalov, Wijk aan Zee 1999

Some games transcend the board. They become stories passed down through generations of chess players, analyzed in cafés and classrooms, replayed thousands of times on screens around the world. Kasparov vs Topalov from the 1999 Wijk aan Zee tournament is one such game.

Garry Kasparov was at the peak of his powers—World Champion, highest-rated player in history, and arguably the greatest chess mind of the 20th century. Veselin Topalov was a rising star, already among the world's elite. What happened between them on that January afternoon would enter the pantheon of chess immortality.

The game earned the nickname "Kasparov's Immortal" for good reason. By move 30, Kasparov had sacrificed two rooks and multiple pawns. By move 35, the Black king had traveled from a7 to d1—a journey of 10 squares across the entire board. It's the kind of game you need to see to believe.

The Full PGN If you want to follow along or run your own analysis, here's the complete game: View the PGN file

The Setup

| White | Black | |-------|-------| | Garry Kasparov | Veselin Topalov | | Wijk aan Zee, Round 4 | January 20, 1999 |

Topalov chose the Pirc Defense, an opening that cedes the center to White in exchange for flexibility. It's not a bad choice—Bobby Fischer used it occasionally—but against Kasparov's aggressive style, it meant walking a tightrope from the start.

1.e4 d6 2.d4 Nf6 3.Nc3 g6 4.Be3 Bg7 5.Qd2 c6 6.f3 b5

Already by move 6, you can sense the tension. Black is pushing on the queenside while White builds a classical center. The stage is set for opposite-side castling and a race of attacks.

The Opening: Building Pressure

7.Nge2 Nbd7 8.Bh6 Bxh6 9.Qxh6 Bb7 10.a3 e5 11.O-O-O Qe7 12.Kb1 a6

Kasparov immediately trades off Black's dark-squared bishop. In the Pirc, this bishop is often Black's best defensive piece—it guards the kingside, supports counterplay, and keeps the position flexible. Without it, Black's kingside becomes vulnerable.

Both players complete their development and castle to opposite sides. This is the pawn-storm setup: whoever attacks faster wins. White's pieces are slightly better coordinated, but Black has counterplay brewing on the queenside.

If you load this position into any chess analysis board, the engine will show rough equality—about +0.3 for White. Nothing dramatic yet. But Kasparov has a plan.

The Knight's Journey

13.Nc1 O-O-O 14.Nb3 exd4 15.Rxd4 c5 16.Rd1 Nb6 17.g3 Kb8 18.Na5 Ba8

Watch the knight on b3. Kasparov maneuvers it: Nb3 → a5, a powerful outpost targeting b7 and c6. This knight becomes a monster—commentators later called it the "octopus" because its tentacles seemed to reach everywhere.

Meanwhile, Topalov has to retreat his bishop to the corner. The pressure is mounting.

The Storm Breaks

19.Bh3 d5 20.Qf4+ Ka7 21.Rhe1 d4 22.Nd5 Nbxd5 23.exd5 Qd6

Topalov pushes d5, trying to free his position. But this only opens lines for White's attack. After the knight exchange on d5, Kasparov has a passed pawn in the center and all his pieces are aimed at Black's king.

Then comes move 24.

The First Sacrifice

24.Rxd4!! cxd4

A full rook for a pawn. Material evaluation: White is down 4 points. Computer evaluation: it takes depth 25+ to understand this sacrifice.

Why is it good? Because Black's king is about to go on an adventure it never wanted.

The King Hunt Begins

25.Re7+!! Kb6

The second rook enters the attack with check. Black has no choice but to move the king forward. This is already unusual—kings generally stay as far from the action as possible.

26.Qxd4+!! Kxa5 27.b4+!! Ka4

Kasparov throws everything at the Black king. The queen swoops in. The b-pawn advances with check. Each move is forcing—Topalov has no time to consolidate.

Let's count the material. White has sacrificed:

- Two rooks (10 points)

- One pawn (1 point)

White has captured:

- Two bishops (6 points)

- One pawn (1 point)

White is down about 4 points of material. But the Black king stands on a4, surrounded by White's pieces, far from safety.

The March Continues

28.Qc3 Qxd5 29.Ra7 Bb7 30.Rxb7 Qc4 31.Qxf6 Kxa3

The Black king continues its forced march: a4 → a3. Meanwhile, White's rook gobbles up the bishop on b7. The position is chaotic, but Kasparov has calculated every line.

32.Qxa6+ Kxb4 33.c3+!! Kxc3 34.Qa1+ Kd2 35.Qb2+ Kd1

This sequence is almost comical. The Black king walks from a3 to b4, then to c3, d2, and finally d1. It has traveled from one side of the board to the other, ending up on White's first rank.

The Finish

36.Bf1 Rd2 37.Rd7 Rxd7 38.Bxc4 bxc4 39.Qxh8 Rd3 40.Qa8 c3

41.Qa4+ Ke1 42.f4 f5 43.Kc1 Rd2 44.Qa7 1-0

Topalov resigned. The final position is hopeless—White's queen dominates the board, and Black cannot prevent checkmate.

Why This Game Matters

I've analyzed hundreds of classic games, and this one stands out for several reasons.

The depth of calculation. Kasparov had to see past move 30 when he played 24.Rxd4. That's at least 7-8 moves of forced play, with multiple variations branching at each node. Even strong engines struggle to evaluate this position quickly.

The artistic quality. A king marching from a7 to d1 is absurd. It shouldn't happen. But Kasparov made it happen through sheer force of will and calculation.

The practical courage. Sacrificing two rooks against a world-class grandmaster requires nerve. Kasparov could have been wrong—one missed defensive resource, and he loses. He trusted his vision.

How to Study This Game

If you want to learn from this masterpiece, here's what I'd suggest:

-

Replay it move by move. Don't just scroll through—play each move on a board and try to guess Kasparov's next move. Where do you agree? Where are you surprised?

-

Analyze the critical moments. Pause at moves 24, 25, 27, and 32. These are the key sacrifices. What happens if Black declines? What happens in the sidelines?

-

Practice the technique. From move 31 onward, try playing out the position against an engine on a reduced difficulty setting. Can you find the checkmate?

-

Compare with other immortals. How does this game compare to Anderssen's Immortal (1851) or Byrne vs Fischer (1956)? What themes repeat?

Looking Back

This game was played over 25 years ago, but it remains fresh. Every time I show it to a new student, their eyes widen at move 25. "Both rooks?!" they ask. Yes. Both rooks.

Chess is often called a game of logic, but games like Kasparov-Topalov remind us that it's also a game of imagination. The greatest players don't just calculate—they dream, they dare, they create.

Kasparov created something beautiful that day in Wijk aan Zee. And we're still marveling at it.

Related Reading

- Fischer vs Spassky 1972 Game 6 — Another world championship classic

- Getting Started with Chess Analyzer — Analyze your own games